CRAI Catalunya Campus / Art Room of Rovira i Virgili University

” THE SINGER / THE SINGER” (A reproduction of this work is annually awarded as the first prize of the “Gràcia Singer-Songwriter Contest” in Barcelona, previously in Tarragona). Technique – Found wood (La Gola del Ter Beach, Pals, Girona) Measurements – 23 x 10 x 9 cm. Museum of Modern Art of the Diputació de Tarragona. Date – TGN. 2008 Photographic archive, Alberich photographers

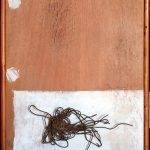

“THE DOLL” (A reproduction of this work is annually awarded as the first prize of the Barcelona Film and Human Rights Festival.) Technique – Polychrome plastic, metal, and wood. Measurements – 26 x 10 x 7.5 cm. Date – TGN 2011 Diputació de Tarragona – Photographic Archive, Alberich photographers

“in the Case of Tapies, as in that of Rosselló, the Hand that Paints also Writes.”

Xavier Barràl i Altet“as for Me, some of Rosselló’s Works I Adore for Their Rawness and Visceral Quality, and the Others, Quite Frankly, I Detest, I Would Burn Them.”

Ricard Planas“from Time to Time, Josep Maria Goes Crazy.”

Ricard Planas“He Manifests His Inner Need to Express Unresolved Conflicts in a Supposedly Stable Society.”

Rosa Ricomà Vallhonrat“He Lays all His Cards on the Table Every Time He Presents His Work.”

Vinyet Panyella“Rosselló Captures the Attention of Visual Arts Lovers for His Inherent Dynamism and for the Reflection that Color Evokes.”

Josep Maria Cadena“Josep Maria Rosselló, in Life and in Art, Deconstructs—in the Derridean Sense of the Word—to Create.”

Antoni Sella i MontserratFrom Automatic Drawing to the Found Object

Text for a conference/exhibition at the Art Room of Rovira i Virgili University in Tarragona, to be held on April 2, 2014.

FIRST PASSAGE

I will begin by clarifying the word. The hows and whys of the title I have chosen for this action I have named “AVARAR”. Avarar is the antonym of varar; that is, if ‘varar’ in nautical language means to stop a ship on land or to run aground, the simple act of placing the vowel ‘A’ before the verb gives it the opposite meaning. Therefore, avarar means to unmoor, to launch a ship into the open sea. In any case, it should not be confused with ‘Avatar’, a word related to metamorphosis, and in recent times, to fantasy cinema.

The word AVARAR appeared when I was actually looking for another word in the dictionary; it captivated me, it seemed suggestive, and while being explicit, it concealed its meaning within its musicality. It equally denotes an event produced by human intervention as by that magical component called ‘chance’, which usually acts freely and at the most unexpected moment. It danced, bold and playful, before my eyes like a white butterfly, but seen against the light, it was a black, dark butterfly, and it gave the sensation of hiding something sinister. It fled through the balcony, bathed in light; later I found it again, on the street, at the four corners of Carrer Major, when I was going to buy the newspaper. And in the evening, at the blue hour of twilight, it returned home and remained imprinted on the first page of this text.

Now, when we have the impression of living in the midst of a collapse, we must try to find a way to launch ourselves again to navigate once more. The sea, sometimes calm, sometimes turbulent, will bring us fortune and adventures, it will bring us life, as it already offered us in other times, and taking a brief look back is a good way to gain momentum and navigate. History is more than a burden we are obliged to drag, and sometimes, to repeat. History reveals to us the roots of many current events, which often feed back into themselves, or are dependent on them due to karmic consequence. “Avarar” places us in the first decades of the 20th century, exactly one hundred years ago, in the avant-garde of that Paris-Berlin of Expressionism, silent cinema, cabarets and music-hall, and also of Barcelona with Wagner’s “Parsifal”, “Furtiva lacrima”, and “Casta diva”, at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, where Circus evenings and Carnival dances were also held. “El cant de la senyera” at the Palau de la Música, and in Paral·lel where daring cuplé stars shone brightly. This is to establish connections between some of the actions of the early avant-gardes and those of our contemporaries.

Yes, that “tout Paris” that applauded Joseph Pujol, “Le Petomane”, that Marseillais of Catalan origin, the famous “flatulist” of the “Moulin Rouge”, who imitated animals and played “La Marseillaise” by farting. It is the same Paris that amazed the world with the Universal Exhibition of 1900, and where in 1907 Picasso painted “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”, Matisse a year earlier had painted “La joie de vivre”, and Gustav Klimt, in secessionist Vienna, painted “The Kiss”.

In 1909, Marinetti published his “Futurist Manifesto” in Italy: “To scandalize becomes a refined luxury, and the greatest risk lies in the voluptuousness of being booed.” In 1913, Marcel Duchamp presented his “Nude Descending a Staircase” in New York, and Charles Chaplin created his most representative character, “Charlot”. Jazz crossed borders; what was still a marginal music, full of primitive rhythms, would soon end up in concert halls, without losing an ounce of its essence. A century was beginning in which everything new would be welcomed.

In Germany, the replacement of the old imperial system by the Weimar Republic plunged the country into a deep crisis of values and thought. Berlin was experiencing a period of intense creativity and experimentation. Expressionist cinema with neo-Gothic atmosphere films like “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari”, starring Conrad Veidt, or “Nosferatu” (Eine Symphonie des Grauens) by Friederich Wilheim Murnau, and Cabaret, which was in its splendor with figures like Claire Waldorff, made cross-dressing an art, so much so that it was said that in Berlin any night flower could well be a man. A good mirror to see what the splendid Berlin cabaret was like, which the Nazis would later ban, is to take as reference the classic German film “The Blue Angel” and its protagonist, the enchanting fairy Marlene Dietrich.

In Barcelona, in 1903, just as “Els Quatre Gats”, the most emblematic venue of Modernisme, which Pere Romeu, from Torredembarra, skillfully managed for six years, closed its doors. The Chinese shadows, puppet shows, literary evenings, and small-format concerts held there vanished, as did the heated disputes among artists during their gatherings. That same year, Picasso painted “La Vie” (The Life), the most significant work of his entire Blue Period. He came to Horta de Sant Joan and Gosol with his wife, and took to Paris, painted, the landscapes that initiated the great Cubist adventure, and which are a banner of classical avant-garde. In 1909, Catalonia burned in the Tragic Week, and the black smoke from the fires rose to the sky, filling it with soot and hearts with rage. And on the other side of the coin, in Paral·lel, “La bella Chelito”, mistress of Alfonso XIII, captivated audiences with the cuplé “La pulga” (The Flea), searching for a flea that had hidden and was hopping among the folds of her dress, and in doing so, performing one of the first “strip-teases” in history. In 1914, Raquel Meller premiered “El relicario” at the “Dorée” in Plaça de Catalunya, and a year later, “La violetera”, the cuplé that would make her famous in Europe and America, at the Arnau Theater in Paral·lel. From “Bataclán” to “Molino”, a “fox-trot” inspired by dandyism resonated, the extreme fashion inherited from Oscar Wilde, which wreaked havoc among artists. “El vestir d’en Pasqual”, premiered by Pepita Iris, was not recorded until 1963, in the voice of the great Mary Santpere.

SECOND PASSAGE

Film director Isaki Lacuesta, at the presentation of his film “Cravan vs Cravan”, said that it was not a Dada film, but a film about the unrepeatable.

Arthur Cravan: Oscar Wilde’s nephew, grandson of the Queen of England’s chancellor, former French boxing champion, sailor in the Pacific, poet, bank robber in Lausanne, hotel rat, car chauffeur in Berlin, etc. And probably, we could add to this long list of professions, that of the first “blogger” in history. One hundred years ago, he directed the historical magazine “MAINTENANT”, of which only five issues were published, quite a success then. He himself wrote each of these five issues entirely, using various pseudonyms, distributing it at the exit of the hippodrome, from a fruit vendor’s cart. He wrote the fiercest art criticism in history, which led to his imprisonment, quite common for the character. He dueled with Guillaume Apollinaire over the publication of a furious text about the painter Marie Laurencin, who was his lover.

In the Paris of Debussy, Ravel, Stravinsky, Falla, Albeniz, Granados, Pau Casals, like a shiver down one’s spine, the mythical javá, Mistinguette’s “Mon homme”, resonated in the streets.

Now, before a new commemorative centenary erupts, one of those that compress everything until it is quite shriveled, if not dissected, I must inform you that on June 5, 1914, exactly one hundred years ago, Arthur Cravan organized a memorable evening at the “Societés savantes” hall in Paris. He danced, he boxed, he fired some shots into the air with his pistol, and he gave great praise to athletes, whom he considered superior to artists; he also praised homosexuals, the Louvre thieves, the marginalized, and the insane.

Afterward, he gave similar “performances” in America, in which, completely drunk, he performed “strip-teases” until the police entered and took him away under arrest. In New York, Marcel Duchamp, under the pseudonym Richard Mutt, presented a urinal titled “Fountain” at the “Exhibition of Independents”; the selection committee, of which he was a member, refused the work, and Duchamp resigned, causing a scandal. On the day of the inauguration, instead of giving a lecture, Arthur Cravan performed a “strip-tease”.

In Barcelona, he fought an already legendary match against the World Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson, at Plaça Monumental. They say that both, by agreement, extended the fight to sixteen rounds because they knew they were being filmed.

In January 1918, fleeing from the First World War, which was nothing new for him, as he had already deserted on several occasions, he met his partner Mina Loy in Mexico; they got married, and since they didn’t have enough money to travel together to Argentina, she went by train, and he rented a sailboat to make the journey by sea. Always the sea. No one ever heard from him again; once launched, he disappeared without a trace, in a truly unforeseen final act, in the Gulf of Mexico. She always waited for him.

In Zurich, in 1916, the first and only issue of the magazine “CABARET VOLTAIRE”, directed by Hugo Ball, appeared, where the name “DADA” was published for the first time. Dada had as its father a letter opener that lasciviously and randomly inserted itself between the pages of a Larousse dictionary, which served as its mother. It broke its own umbilical cord with everything that tied it to the art of the past, and sought to restore the word to its true original meaning. The Dadaists rediscovered the brilliant poet Arthur Rimbaud, who had died twenty-six years earlier, and this fact, along with the fresh air that Arthur Cravan had let in by kicking open the rusted door of academicism, grants it its Parisian origins.

An intense crisis of values, the outbreak of the First World War, and the deep rage of those young people pushed them towards destruction. In the words of André Gide: “Dada is a demolition enterprise.” Order and Chaos, Destruction – Premonition. Fusion of art with life, and making every moment a celebration; creation distanced from life produces conventional art, hence Dada, in a brave attitude, seeks remedy in destruction and makes destruction an act of creation. Dada sweeps away academic constraints and gives rise to almost all artistic movements of the 20th century. Its anti-cultural, counter-cultural propaganda, its texts, and its actions, are born from honesty and disgust at the affected superiority of established intellectuals.

The leaflets distributed in Paris in May ’68 were very close to the violent language of the Dadaists; even when they invite us to reflect, to give words their real meaning, they use language that recalls some of the protest songs of the Revolution.

In full Dada activity, among the marginal circles of Parisian artists, another magical word was already beginning to be whispered: “SURREALISM”, linked like an invisible umbilical cord to automatic writing.

But although we speak of them now, their proposals having been accepted, it must not be forgotten that for the society of their time, they were merely practically non-existent subversive groups, and thus, stale academic tastes found fertile ground in a society little disposed to adventure. In the words of art critic Santiago Amón: “It has been said, and not without reason, that Dadaism, of clear vitalist origin, clashed in Europe with ‘bourgeois rationalism’, and it has been omitted that the true confrontation occurred with other avant-garde artists.”

In Berlin, in 1919, the Bauhaus School began its activities in Weimar. The anarchist attitude against art and the bourgeoisie had radicalized, provoked by class struggle and the disastrous end of the war.

Finally, women found their place in the world of art; new trends opened the way for them, without any exclusion, and without differentiating it from art produced by the male world. In Catalonia, the magazine “L’Amic de les Arts”, published in Sitges, echoed the avant-garde in European plastic and literary arts, and opened the doors to a new world with articles by Josep Carbonell i Gener, Lluis Montanyà, J.V. Foix, and the young and daring Salvador Dalí and Federico García Lorca. It published the “Yellow Manifesto”, with clear influences from other manifestos previously published in France, Germany, and Italy. In Barcelona, the Dalmau galleries became the reference point for contemporary art of the first quarter of the century. It was around these years that Joan Miró, the quintessential Fauvist-Surrealist plastic artist, painted “The Farm” (La masia), in Mont-Roig del Camp, and a couple of years later, the suite of “Harlequin’s Carnival”. Salvador Dalí painted “Honey Is Sweeter Than Blood”. Foix wrote a collection of poems that he would publish later and titled “Sol i de dol”.

In Berlin, after more than forty rehearsals, “Pierrot Lunaire” Op. 21, with music by Arnold Schoenberg, based on a poem by Albert Giraud, premiered. An expressionist work, incorporating a new way of understanding diction, “Sprechstimme”, between recitation and singing, something that places it within Dadaism and among the precedents of Surrealism.

Dada fed on all cultures, drank its own potion to complete intoxication, was and is a catalyst, not only for artists, but for humanity. Its violent character confuses, becomes unclassifiable, and ends up devouring itself. Tristan Tzara, in the 1918 manifesto, writes: “It has been demonstrated that the purest means of proving love for another is to eat them.”

A German soldier who had been transferred to the Russian front in 1915, during the First World War, wrote a poem titled “Lili Marleen”; in the 1930s, Norbert Schulze set it to music, and that is how the song was born that thousands of soldiers from both sides would later sing during the Second World War.

Many Dadaists, lost in the anarchic lack of rules, became adherents of Surrealism. Marcel Duchamp, however, did not: “The most acceptable system is to have none, on principle.”

In Barcelona, in 1917, Francis Picabia published the magazine “391”, in collaboration with André Breton and the gallerist Josep Dalmau; it was also published in New York, Zurich, and Paris. With clear influences from the New York-based “291” published by Alfred Stieglitz, nineteen issues appeared until 1924. Aggressive in tone, Dada had important collaborations: Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Tristan Tzara, and Jean Cocteau. In Picabia’s words: “Art must be extremely unaesthetic, useless, and impossible to justify.”

“Les Mamelles de Tirésias” (surrealist drama), written as a play by Guillaume Apollinaire in 1903, premiered a couple of years later and was a scandal. Converted into an opera by Francis Poulenc, it was re-premiered in 1947 at the Opéra-Comique in Paris. It is an opera buffa with feminist and anti-militarist undertones, with an evident change of roles, male-female. For the first time, something was defined as “surrealist”. In Apollinaire’s words: “When man wanted to imitate the act of walking, he created the wheel, which in no way resembles a leg. And that is how he made surrealism without knowing it.”

In Berlin, George Grosz produces drawings imbued with biting social criticism, portraying the effervescent and marginal atmosphere of the 1920s, the interwar period of the Weimar Republic, and the rise of Nazism, when Berlin was still a vibrant scene.

It is the golden age of the Ballets Russes, directed by Sergei Diaghilev, with the legendary dancer Nijinsky. In 1917, Jean Cocteau wrote “Parade” commissioned by Diaghilev, with a libretto by Apollinaire, sets by Picasso, and music by Erik Satie; its premiere was a monumental scandal. Jean Cocteau is another artist from Dada to Surrealism who never belonged to any of the Parisian groups or factions. His poetry and filmography, as well as his drawings, place him among the great representatives of the movement.

In Paris, in 1925, the “Revue Noire” or “Revue Nègre” premiered, in which a very young Josephine Baker danced in a banana skirt that drove the audience wild. In the same year, it also premiered in Berlin.

In 1929, Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí premiered the film “Un Chien Andalou” with great success at “Studio 28” in Paris; the fact that it was a success did not please Dalí at all. A year later, they premiered “L’Âge d’or,” which this time, indeed, caused an epic scandal. In the lobby, works by Joan Miró, Henri Masson, Max Ernst, and Man Ray were exhibited; none remained intact, as far-right groups damaged them all and destroyed part of the cinema, while the audience tore out seats and threw them at the screen on which the film was being projected.

The poet Federico García Lorca embarked on a journey to New York aboard a transatlantic liner, fleeing the unprecedented success of his poetry book “Romancero Gitano”. In the great city, he would write the most powerful collection of poems of the 20th century, “Poeta en Nueva York,” and one of the most transgressive works of his unrepresentable theatre: “El Público,” written between New York and Cuba, works that seem to be indelibly marked by the tragedy of modern man and are a permanent echo of the avant-garde.

THIRD PASSAGE

CHANCE—————ENCOUNTER—————-PASSION, define surrealism in one way or another. But let no one be mistaken, let no one claim to be its father; if we scratch a little, we will find precedents among the Romantic poets, the Symbolist painters and poets—Arthur Rimbaud was one—even among the troubadours of the 11th to 13th centuries, who transgressed norms by unveiling the language and spirit of passion. Guillaume Apollinaire gave it the name, André Breton encountered it. He considered automatism the supreme key to the marvelous, but he too could not escape the curse: destruction, in this case due to excessive dogmatism.

Automatic writing, performed in a trance state, probably has roots clinging to archaic cultures, but at the beginning of the 20th century, it is related to the spiritualist sessions held in the select private salons of many European, and especially Parisian, homes. In fact, it sought nothing more than to pave the way between two seemingly antagonistic worlds, the physical and the psychic, without any censorship, to connect the hidden dark side and the luminous, and thus open the barred doors of perception, and by the same path, in the same way, and with the same tools: paper and pencil, automatic drawing emerges as if by magic.

To walk, aimlessly, without any destination, to walk. To look, to observe, a characteristic trait of the Surrealists, as it had previously been of the Romantics, of whom they are undoubtedly heirs. And once again, the dazzling and erratic presence of Arthur Rimbaud, and those constellation-like and searing poems that amazed his contemporaries and continue to fascinate us. To walk, to wander. To peer into cafes, into shops, to gather wood, stones, and various debris on pristine beaches and along paths, to sail on the open sea, and adrift, in an inevitable behavior unconsciously linked to chance, in which the strange bond between all things and oneself becomes evident, in search of something marvelous, unexpected, chance, something perhaps only intuited. Breton’s “L’amour fou”. It is from here that the found object is born, the treasure, which is generally nothing exceptional, except for the one who finds it, and who in a passionate impulse takes it home, perhaps secretly, hidden under a coat, without knowing why, an act surrounded by mystery and a certain morbidity that brings it close to sin. Or…perhaps it is the other way around, perhaps it is the object that emanates a magical fluid, a spark, and it is the object that chooses the artist who will make it marvelous in the eyes of others. What for anyone else was merely junk, becomes a work of art.

The artist, if skillful, while fully respecting the find, must be very careful in its manipulation, so as not to damage the essential features that have captivated them and make it so precious, features that can be ruined by the excesses provoked by passion.

Now, digital photography, with its immediacy and brilliant resolution, allows us to dispense with the original object, and thus it will become part of an archive of singular finds, even though the physical object is what holds the magnetism that makes it special. This does not mean that it is not possible to photographically capture even the most subtle aspects and transmit them. Man Ray did so and gave the vulgar object the dignity of a work of art.

Sometimes, years can pass, and the found object, as well as the untouched drawing, remain so fascinating that the artist does not know how or where to begin working on it, for fear of losing its initial magic; the same can happen with a splash of color on paper or canvas, also to the poet, who sometimes may not find the exact word that will give meaning to the verse for a long time, and to the musician. But one day, perhaps at dusk, or under a radiant starry sky, on any street, perhaps in full sun, or in the rain, in any conversation, or at any turn, they find the way, find the word, the title, or the note that had been hidden from them for so long, and the ship, finally launched, sails.

LET’S GO TO INSTINCT, LET’S GO TO CHANCE, TO PURE INSPIRATION, TO THE FRAGRANCE OF IMMEDIACY

————————————-Josep Maria Rosselló-, Three Kings’ Night, 2014————————————-

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“DADA, History of a Subversion,” Henri Béhar, Michel Carassou. Edicions 62, “Península”. Barcelona 1996.

“L’amour fou,” André Breton. Editions Gallimard, Paris 1937.

“Manifestos of Surrealism,” André Breton. Ed. Guadarrama, university collection Punto/ Omega 1975

“Sketch of the New Painting,” Federico García Lorca. O. C., 1928

END

Photographs: Diputació de Tarragona. Photographic Archive, Museum of Modern Art. Alberich photographers